Peer-reviewed articles

“Setting History in Motion: Social Movements and Popular Art in Urban Brazil, 1970s-1990s,” American Historical Review 129, no. 4 (December 2024): 1703-1731.

Abstract: This article examines the video essay in this issue, “Visualizing Resilience from the Periphery: Social Movements, Visual Archives, and the Megacity,” and the video essay as a form of historical argumentation. First, the article traces how the video essay reconstructs a visual lexicon that fostered resilience among social movements from the urban peripheries of South America’s most populous city, São Paulo, during Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship (1964–85) and the democratic transition that followed. Popular artists illustrated movement paraphernalia with hand-drawn images of diverse subjects, including urban landscapes, public life, neighborhood organizing, and open protest. The video essay assembles these dispersed illustrations as well as soundscapes and clips from films into distinct phases of a metanarrative connecting the rise of the megacity to collective social action. It subsequently disassembles those focal points to underscore the open-ended and iterative nature of visual argumentation. The article then underscores how the video essay as a form of peer-reviewable argumentation allows historians to creatively engage with a large corpus of visual imagery. It concludes by discussing issues inherent to the form, such as the difference between written and visual argumentation, citation practices, integration of text, translation of foreign languages, and the preservation of digital scholarship, among others.

“Visualizing Resilience from the Periphery: Social Movements Visual Archives, and the Megacity,” American Historical Review 129, no. 4 (December 2024).

How do visual imaginaries shape resilience? How might historians experiment with form to analyze visual sources? The video essay Visualizing Resilience from the Periphery addresses these questions, employs visual argumentation based on Urban Intermedia to explore how popular artists used imagery to foster resilience among social movements from the urban periphery of São Paulo, South America’s most populous city. Across Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship (1964–85) and the subsequent democratic transition, these movements organized to demand basic urban infrastructure and essential state services. This activism generated a vast archive of flyers, bulletins, pamphlets, and comic books adorned with hand-drawn illustrations by mostly anonymous artists that depicted the city and social action. The video essay combines these illustrations with clips and soundscapes assembled from activist films to reconstruct distinct moments of a linear metanarrative that envisions everyday people rising to confront inequality in the megacity. These illustrations went beyond simply supporting movements through visual representations of grassroots organizing. Taken together, the illustrations comprised a collective act of world-building by popular artists from the margins of a megacity. The companion essay that follows explores the stakes of visual argumentation for the construction of social resilience by historical actors and reflects on the visual essay as a framework for historical analysis.

“Grassroots Archives: Memory, Dictatorship, and the City,” American Historical Review 129, no. 2 (June 2024): 669-680.

Abstract: In recent years, coalitions of activists, artists, scholars, and community members have created archives composed of material related to social movements past and present with increasing frequency. These grassroots archives raise questions about the potential role of archives as generative spaces for democratizing history. This article explores this potential and the attendant challenges through a case study on an effort to preserve the memory of activism in São Paulo’s urban peripheries during Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship (1964-85) in which the author took part amid the rise of the far-right wing president and former dictatorship supporter Jair Bolsonaro. The post-dictatorship culture of censorship and an ever-changing city relentlessly militated against the permanence of memory, not least through the destruction of physical archives and reference points in the urban landscape. The effort to organize and digitize precarious materials unfolded amid a larger campaign by activists to create an archive as part of a new university in the periphery. In this article, the author reflects on his experience working with communities through grassroots archiving to preserve at-risk historical sources, enhance local capacity, and broaden the practice of history beyond the academy.

“São Paulo Rising: Grassroots Movements and the Right to Health in Authoritarian Brazil,” Hispanic American Historical Review 103, no. 3 (August 2023): 495–526.

Abstract: This article examines grassroots constructions of a right to health in São Paulo's urban periphery during Brazil's civil-military dictatorship (1964–85). Centered on the rise of the Movimento de Saúde da Zona Leste (Health Movement of the East Zone), an agglomeration of neighborhood health movements, the article explores how grassroots movements came to articulate a notion of a right to health that incorporated the right to shape the city and the right to democratic participation while under military rule. As frustration with a lack of sanitary infrastructure and poor-quality health care mounted, grassroots movements organized neighborhood health commissions and compelled the state government of São Paulo to recognize elected popular health councils as comanagers of public health-care facilities. In tracing this trajectory, this article demonstrates that health was a key area through which everyday people negotiated the contours of Brazil's emergent democracy during the transition from authoritarian rule.

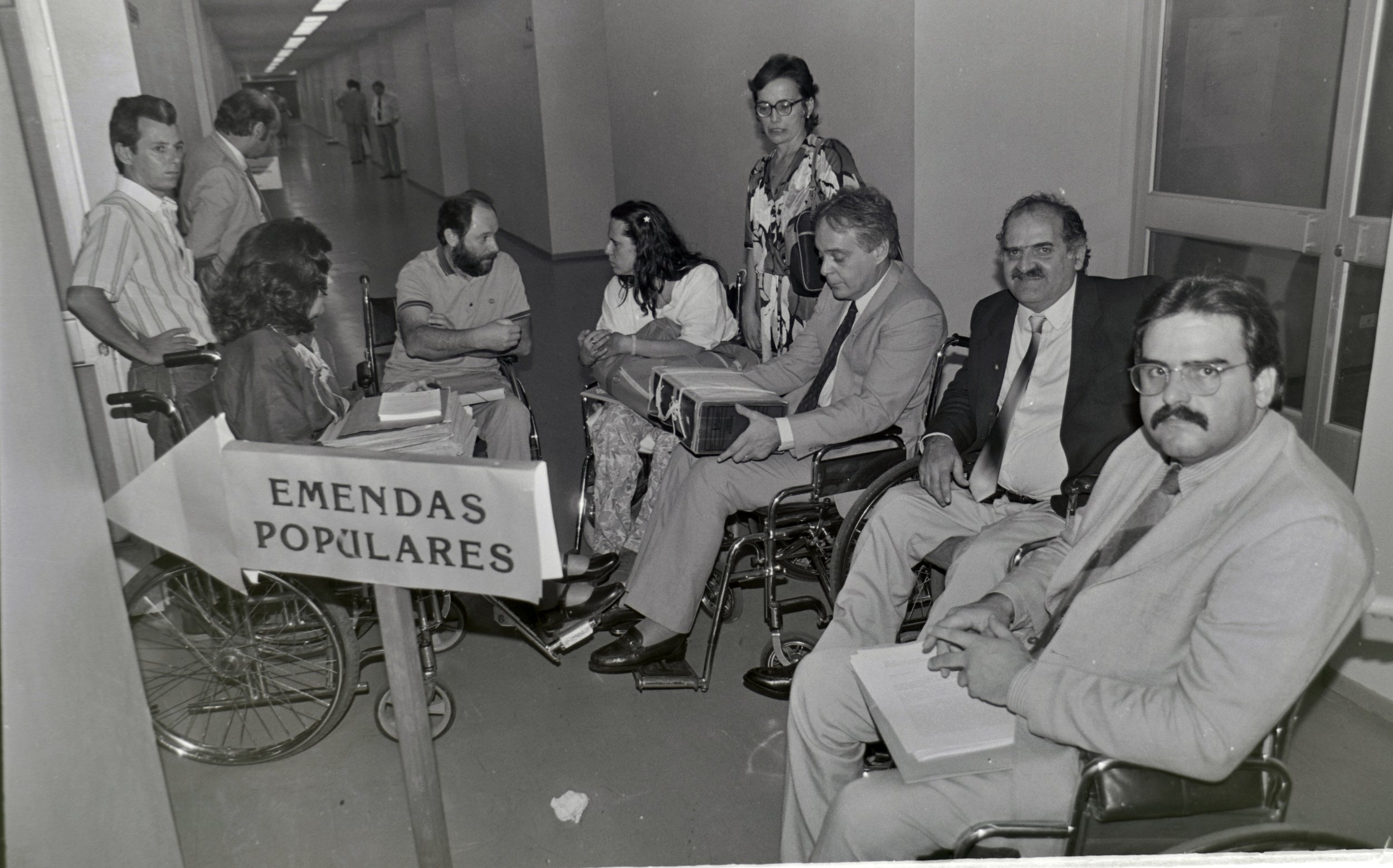

“Making the "Citizen Constitution”: Popular Participation in the Brazilian Transition to Democracy, 1985–1988,” The Americas 79, no. 4 (October 2022): 619–52.

Abstract: This article examines popular participation in the making of Brazil's 1988 post-authoritarian “Citizen Constitution.” In 1987, Brazilians submitted 122 popular amendments (emendas populares) supported by over 12 million signatures to the National Constituent Assembly (1987–88). As this article contends, this extraordinary experiment in popular constitution-making problematizes notions of Brazil's transition from authoritarian to democratic rule as the most conservative of those that swept Latin America at the end of the Cold War. The popular amendments emerged amid a nationwide campaign for popular participation that saw millions of Brazilians participate in letter-writing campaigns, protests, and debates over the constitution that carried over into the halls of the Constituent Assembly itself. I argue that the popular amendments countered the arbitrary authoritarianism of the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship (1964–85) with a constitutionalism in which everyday Brazilians would safeguard democracy through popular participation in government. While only partially consolidated, this vision offered diverse marginalized groups an opportunity to claim full citizenship in Brazil's nascent democracy, especially in ways that more overtly addressed issues of race, ethnicity, gender, and disability. This article thus shows that far from being the exclusive province of political elites, everyday people meaningfully shaped the constitutional restorations in late twentieth-century Latin America.

“The Origins of Informality in a Brazilian Planned City: Belo Horizonte, 1889-1900,” Journal of Urban History 47, no. 1 (January 2021): 29–49.

Abstract: Sixty years before Brasília, Belo Horizonte was constructed as Brazil’s first modern planned city (1894-1897). This article focuses on the role of land development in shaping inequality in Belo Horizonte, the first of four major planned cities in Brazil. In Belo Horizonte, political backers and urban planners viewed controlled land development as providing a clean break with the past and creating an industrial, Eurocentric modern future in the wake of the abolition of slavery (1888) and the end of Brazil’s post-independence empire (1889). This article argues that more so than the architecture of its buildings or its urban plan, Belo Horizonte modeled an “architecture of capital” in which creating an urban property market both emerged from and was tasked with producing the city’s racialized narrative of modernity and progress. Belo Horizonte’s emphasis on land speculation gave rise to one of Brazil’s first favelas, comprised of the workers tasked with constructing the city.